The Quiet Divide: Hospitals, Power, and the Law

Is the prison hospital a shield for privilege?

COMMENTARIES

Asanga Abeyagoonasekera

9/6/2025

Pic: Former State Minister Shasheendra Rajapaksa, who is currently in remand custody, has been admitted to the Prison Hospital.

Is the prison hospital a shield for privilege?

In this island fractured by politics and power, where protestors still gather in the streets of Colombo, the hospital has taken on a role beyond healing. For some, it has become a refuge—a softer alternative to the harshness of a prison cell. Those with influence, a name, or simply the means to afford connections are often escorted not to the cold floor of remand, but to a prison hospital. Here, comfort tempers consequence, and justice wears a different shade.

The recent arrest of a former head of state, a six-time prime minister reveals this truth starkly. The law of Sri Lanka is strong; it now applies to all citizens, even the most powerful. Ranil Wickremesinghe, long seen as untouchable, was taken into remand and admitted to ICU when genuinely ill—a reminder that justice can uphold dignity without prejudice. Yet the law does not operate in isolation. Cultural expectations, entrenched privilege, and the remnants of political power still distort its application.

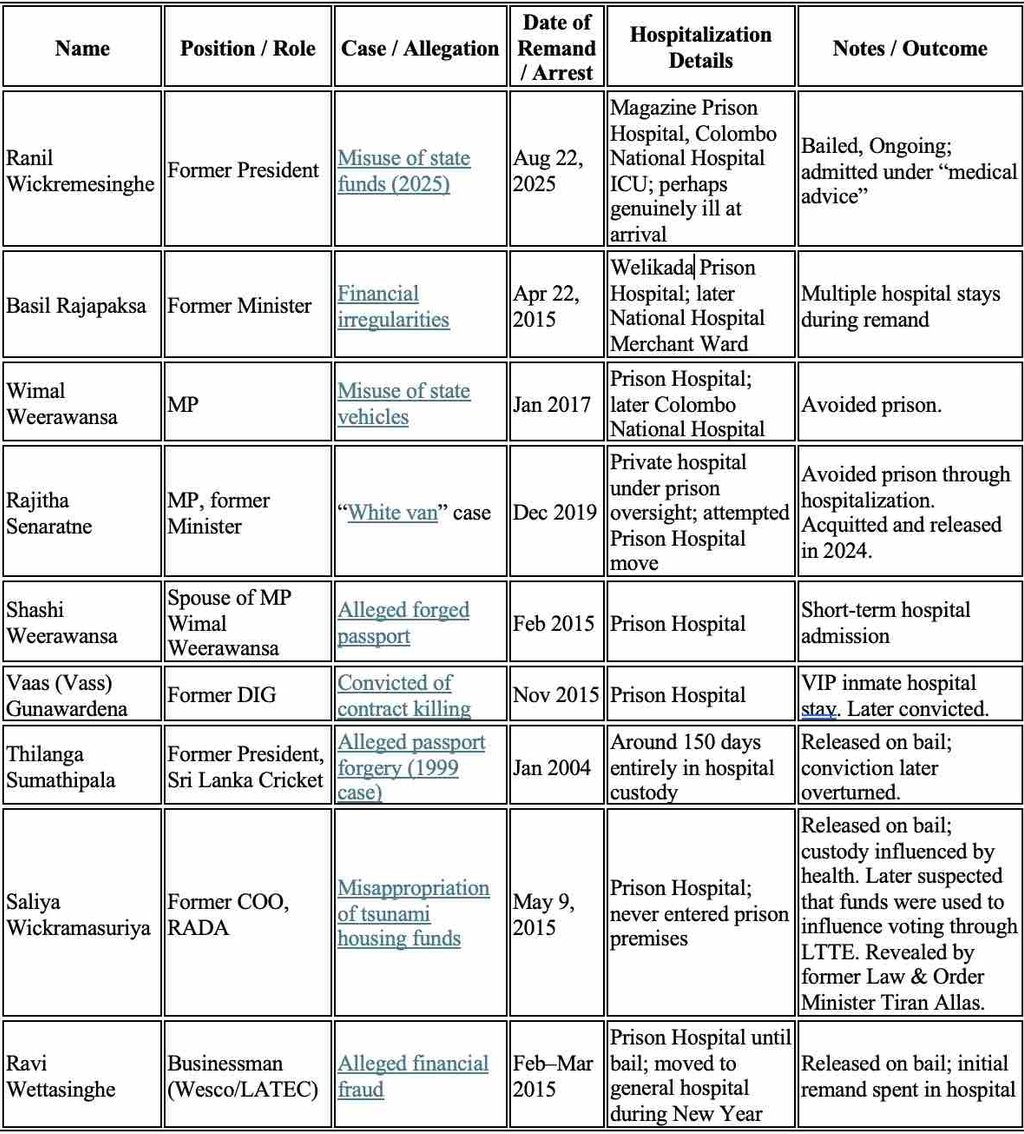

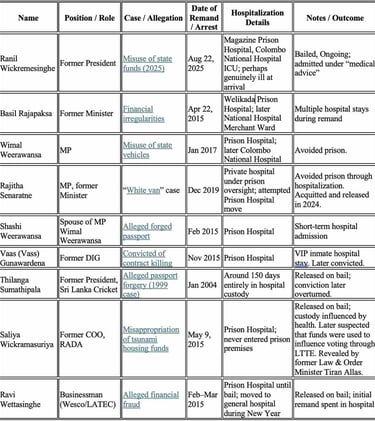

The pattern is familiar. Basil Rajapaksa, Wimal Weerawansa, Thilanga Sumathipala, Saliya Wickramasuriya, Ravi Wettasinghe—the list continues (see Table 1.0). All were admitted to hospital under remand. These episodes do not reveal a weak law, but the barriers that obstruct its execution. Society struggles to reconcile respect for status with the demands of justice. A former president’s spouse accused of financial crimes may never face full scrutiny—not because the law is absent, but because politics and culture intervene. Too often, such cases are dismissed as “witch hunts,” framed as vendettas rather than accountability.

The prison hospital, in fact, has become a refuge not just for the affluent elite but for anyone with the resources, networks, or social position from the lower middle class upward. For the poor, it remains out of reach. They endure the full weight of overcrowded prisons and inadequate healthcare while others secure the comparative comfort of hospital beds. The joint opposition’s rush to shield Wickremesinghe underscores a deeper question: can Sri Lanka’s political rivals ever hold each other accountable?

Opposition politician Mano Ganeshan captured this imbalance with unsettling clarity. Speaking on Wickremesinghe’s release, he claimed he opposed Wickremesinghe’s record on the Central Bank bond scam and the torture chambers of Batalanda, but nevertheless supported his present case. He even dismissed misappropriation of public funds as a minor act, common among affluent families. In effect, he weighed one crime against another to justify support—an act itself unacceptable in the eyes of justice.

Sri Lanka is not unique. In Thailand, a single phone call once toppled a prime minister—proof not of weakness, but of law applied at the highest level. In Sri Lanka, Wickremesinghe himself was ousted by former president Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga, who accused him of secretly handling the Norwegian peace deal with the Tamil Tigers. Even then, law and politics were inseparable.

Of course, Wickremesinghe may well have been gravely ill upon his arrival at prison. The law rightly entitled him to medical treatment, as it does any citizen. But the episode also illuminates the delicate balance between human rights and accountability.

I remember another man from my cell during my own arrest last year. He had stolen copper wire worth Rs. 22,000 (USD 75) to feed his mother. “I had no money to send her,” he told me. “I stole from the factory where I worked. No lawyer will help me. I have only one option now: to drink poison.” For him, the prison hospital was an unreachable dream—not because the law denied him care, but because inequality decided what he could access.

The contrast is stark. Wickremesinghe stood shielded by three hundred lawyers; this man had none. Injustice in Sri Lanka lies not only in the enforcement of law but in a society where privilege dictates who receives dignity and who suffers in silence. As Minister K.D.Lalkantha said of his own arrest: “We too were taken in for political reasons, but we did not bend our backs to secure bail.”

The courtroom offers another glimpse of this imbalance. When I was granted bail, thirty prisoners were crammed into a single cell with one open toilet, waiting for their names to be called. Overcrowding, inadequate facilities, and underpaid prison officers all hinder humane justice. Corruption cuts both ways: among the accused and those tasked with enforcing the law. Singapore’s former prime minister Lee Kuan Yew, often cited as a model, addressed this with fair salaries for officials. Sri Lanka still struggles, though the machinery of law pushes forward. Today, under a president who has pledged not to turn back, justice has reached even those once thought untouchable.

Still, society hesitates. A former IGP is caught treasure hunting with his wife. Former minister Rajitha Senanayake disappears despite asset seizures, only to reappear in court smiling for cameras as if performing on stage. In each case, the law proves capable of acting, yet social, political, and logistical obstacles delay its force. Too often, the prison hospital has been exploited—not as a place of care, but as a sanctuary for privilege, from the lower middle class upward, while the poorest endure the system in full. The prison hospital cannot be allowed to serve as a de facto shield for the privileged—like in the past, when one wealthy inmate even painted its walls as an act of “charity” during his arrest.

Reform is therefore essential. The IMF’s Governance Diagnostic Report recommended establishing an independent prosecution office—an initiative Justice Minister Harshana Nanayakkara has begun with support from civil society groups such as the CPA. Such reform could clear systemic bottlenecks and ensure that high-profile figures are held accountable without delay.

The prison hospital must not remain a shield for privilege, nor a charity project for the powerful in their hour of reckoning. Its gates should open only for the genuinely ill, not the socially protected. Only then can the law operate to its fullest, ensuring fairness amidst structural and cultural challenges.

On this island, the hospital, the courtroom, and even the land itself reflect inequality. They reveal the barriers the law must navigate. Yet the law remains steadfast: it can reach the powerful, enforce accountability, and uphold justice. Until privilege, culture, and weak institutions are confronted, the affluent and even the lower middle class may continue to escape the system’s harshest realities, while the poor suffer without recourse. The law itself endures—waiting for society to give it space to act without compromise.

(Table 1.0) Selected High-Profile Accused Who Utilized the Prison Hospital in Sri Lanka