Winds of Change in the Year of the Horse: Taiwan and Sri Lanka at the Indo-Pacific’s Center

As the Chinese calendar turns to the Year of the Horse (馬), the Indo-Pacific enters a moment of quiet reckoning. History rarely announces itself here. It does not arrive with declarations or ceremonies. It moves like the monsoon..

COMMENTARIES

Asanga Abeyagoonasekera

1/1/2026

Pic: Painted pottery horse, Tang dynasty (A.D 618 - 907) Henan Museum. Photographed by Asanga Abeyagoonasekera (May 15th 2025)

As the Chinese calendar turns to the Year of the Horse (馬), the Indo-Pacific enters a moment of quiet reckoning. History rarely announces itself here. It does not arrive with declarations or ceremonies. It moves like the monsoon—slow, deliberate, reshaping the shoreline long before the storm is visible. When nations finally notice the water at their feet, the change has already taken place.

That moment is now.

Beginning in 2026, nearly $40 billion—the largest defense allocation ever committed to the Indo-Pacific—will be directed toward deterrence, air defense, and emerging military technologies. This is not merely a budgetary exercise. It is an admission of unease. What was once abstract has become tangible. China’s proximity is no longer a concept but a presence. Plans for a Taiwan air-defense “dome,” accelerated investment in drone warfare, and autonomous systems—outlined in a Harvard report—signal the end of distant hypotheticals. The strategic clock is no longer silent; it can be heard.

RAND points to 2027, the centenary of the People’s Liberation Army, as a potential inflection point. Yet, in a crowded restaurant in Bangkok, a senior Chinese analyst offered a more unsettling thought. “Sooner is better,” he said, calmly. There was no provocation in his tone—only confidence. The $40 billion escalation is not anticipation; it is response. For those closest to power, risk has already taken form.

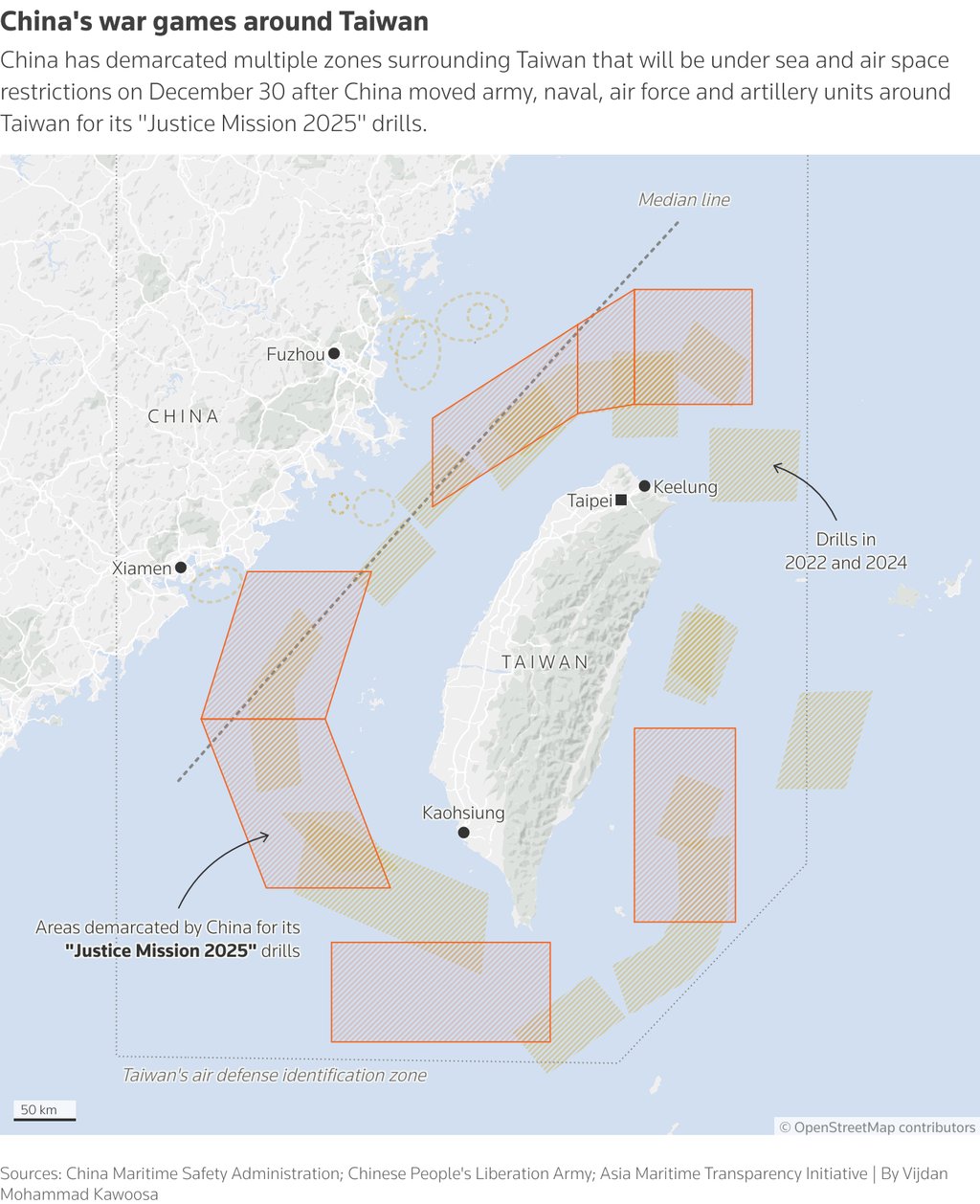

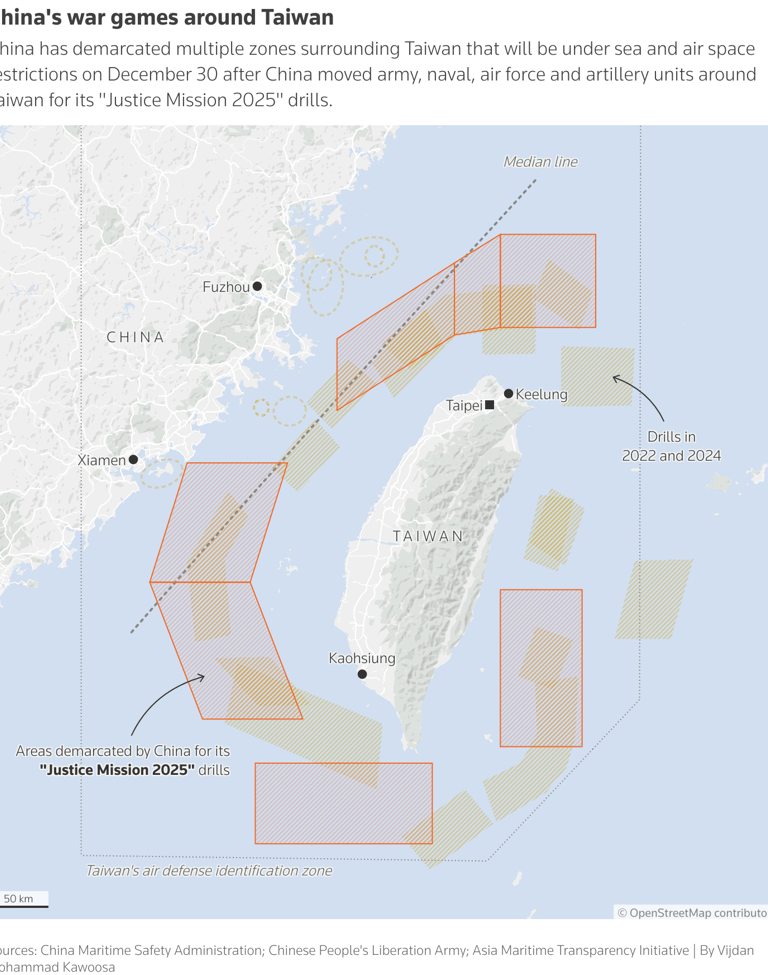

Eleven days after Washington announced the $11b defense allocation—and only days before the new year—China commenced its largest live-fire war-gaming exercise to date. Branded Justice Mission 2025, the drills covered unprecedented geographic scope and unfolded closer to Taiwan than any previous exercise. The timing was not coincidental. It signaled that while strategies are debated in capitals, power is already being rehearsed at sea.

The asymmetry is stark. Washington’s attention is divided across multiple crises—Ukraine, Iran, Venezuela, ISIS in Nigeria. Beijing faces no such diffusion. Its focus remains fixed on its maritime periphery. One watches the world; the other watches the shoreline.

Two islands—Sri Lanka and Taiwan—sit quietly within the Southeast Asian geosphere, near the exposed center of the Indo-Pacific. They are not alike in history, ideology, or scale, yet they share a condition: each lies closer than comfort allows to two emerging powers. Geography, indifferent to intention, has placed them where great powers pass through rather than settle. In such places, neutrality is rarely respected for long.

As I argue in Winds of Change, when the center of gravity tilts toward the Middle Kingdom, the periphery does not resist indefinitely—it adjusts. Not always by choice, and rarely without cost. Influence moves outward with patience, until what once seemed distant becomes unavoidable. The island does not decide the tide; it only learns how to live with it.

The regional balance is tilting. The United States has a narrowing window to shape what follows. President Trump’s National Security Strategy reflects this awareness. It is blunt, unadorned, and therefore revealing. Strategic ambiguity, once a useful instrument, has become a liability. Allies are now asked—not gently—to do more, to carry more, to assume responsibility in countering both China and Russia.

Sri Lanka, long treated as peripheral, has emerged as a quiet hinge in this architecture. The newly formalized U.S.–Sri Lanka defense Memorandum of Understanding is not ceremonial. It is geometry. It coincides with China’s expanding confidence across Southeast Asia, marked by diminishing restraint. The U.S.–China Economic and Security Review Commission makes the reality plain: Beijing is no longer simply rising; it is redesigning the political, economic, and maritime order of the region.

For Washington, this moment demands clarity. The call for “reciprocal diplomacy,” anchored in fairness rather than assumption, reflects a recognition that the post–Cold War framework—built on imbalance disguised as goodwill—has reached its limits. Reciprocity is not retreat. It is acknowledgment. As Oren Cass argues persuasively in Foreign Affairs in his essay on a grand strategy of reciprocity, sustainable order rests not on unilateral generosity, but on mutual obligation and shared responsibility.

Sri Lanka sits astride the Indian Ocean’s most vital sea lanes, exposed and consequential. Partnerships linking the island to the Montana National Guard and the U.S. Coast Guard are not bureaucratic footnotes. Joint maritime training, aviation coordination, disaster response, and enhanced domain awareness form the scaffolding of resilience. Earlier agreements—the ACSA, SOFA, and the India–Sri Lanka defense MOU—draw Colombo firmly into the Indo-Pacific security orbit. These are preconditions for balance, not provocations.

This architecture also counters subtler pressures across the Indian Ocean: economic leverage, strategic port access, illicit networks, and information influence. As U.S. Ambassador Julie Chung has observed, such agreements strengthen peace precisely because they reduce vulnerability.

India, the region’s strategic hinge, has moved decisively. The recent visit of Dr. S. Jaishankar, India’s Minister of External Affairs, to Sri Lanka was not routine diplomacy. It signaled New Delhi’s intent to anchor the island within a rules-based order—one that privileges sovereignty, transparency, and balance. In a region where ambiguity breeds exposure, presence itself becomes policy.

India’s role as a “First Responder,” underscored by over $450 million in assistance and its intervention during Sri Lanka’s 2022 bankruptcy, reinforces this intent. Modi’s Neighbourhood First and MAHASAGAR initiatives seek to lock in Sri Lanka’s strategic alignment. At the same time, officials of the Chinese Communist Party speak of “rebuilding Sri Lanka,” reminding observers that influence rarely arrives unopposed.

I have observed these shifts over three years of research across South and Southeast Asia, captured in my forthcoming book Winds of Change (World Scientific, 2026). China’s advance is not episodic; it is methodical. Trade corridors align with port access. Political influence leverages debt and elite capture. Cyber infrastructure embeds itself in critical systems. Supply chains redirect dependence. Media narratives normalize inevitability. Power here is patient.

Southeast Asia senses this shift. Surveys from ISEAS reveal a familiar ambivalence: governments recognize China’s economic gravity but distrust its intentions; they welcome U.S. engagement yet question American staying power. This skepticism is rational. Washington’s signals have fluctuated. Beijing’s ambitions have not.

Maritime security remains the Indo-Pacific’s central axis. Through the South China Sea flows the pulse of global commerce—energy, food, manufactured goods. When this balance tilts, it is not only a region that changes; global norms shift with it.

This is why the United States, alongside India and regional partners, must restore and expand its maritime posture—not as provocation, but as preservation. Security today depends not on empires, but on networks. No single nation—India, the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore—can carry this burden alone. Cooperation has become the only durable form of power.

The Indo-Pacific now stands where evidence and strategy converge. China’s expanding influence, the warnings of the Commission report, and the fragile coordination among democratic partners are threads of a single fabric. The question is not whether that fabric will be woven—but by whom.

The Winds of Change move quietly across these waters. What remains uncertain is whether Washington, New Delhi, Colombo, Manila, Taipei, Hanoi, Singapore, and Jakarta will heed their direction—before the tide turns, silently and irrevocably, for good.

Asanga Abeyagoonasekera is Executive Director of the South Asia Foresight Network under the Millennium Project in Washington, DC. He is the author of Winds of Change: Geopolitics at the Crossroads of South and Southeast Asia(World Scientific, 2026).